It's that magical time of year again, interview season at medical schools across the country! For those unfamiliar with the archaic system that is the medical school application process, I'll try to provide a quick summary. Essentially all med schools require applicants to take certain classes to be eligible, then all applicants take a standardized exam called the *name deleted to protect would-be applicants from themselves*. Then, typically following their junior year of undergrad, applicants submit a standardized "primary" application to any school of their choosing through a national computer program. This includes a personal statement that is invariably embarrassing and chock-full of half-truths, a list of impressive-sounding extracurriculars and awards, and your transcript and standardized test score. Did I mention that submitting the primary application and taking that test costs buckets of money? Ok, good.

At this point, the schools check out your goods along with thousands of other applicants. Then they choose a subset of applicants to further query in a "secondary" application with school-specific questions and requested information, including a small photo of yourself (which I'm sure are treated by the admissions personnel with nothing but respect and never, ever become running jokes in the office). This is largely a huge pain in the applicant's ass, which is undoubtedly the only reason to make these mandatory. I feel I should mention in passing that the schools all charge an additional fee (which averages to about $75 or so) to consider these secondary applications when you turn them in. Oh, and most successful applicants apply to anywhere between 12-15 schools, with some crazies applying to over 40 of the 120 or so schools across the country.

The schools' admissions committees then review each applicant individually, and if their review is favorable they will invite them for an interview at the school. This requires the applicant to travel to the school while taking time away from work or their senior year of undergrad to spend a full day learning about the school via tours, Q&A sessions, and countless powerpoint presentations. The applicant is responsible for the airfare, the business attire required at the interview, and usually lodging costs, all for a chance at the coveted role of

MEDICAL STUDENT. Did I mention that medical school tuition usually leaves graduating physicians with over $200,000 in debt? But let me be fairhanded in this tale: the medical school

is kind enough to provide lunch during the interview day. Although chances are your nerves will be far too rattled to actually allow you to enjoy a meal. Life can be such a cruel, cruel mistress.

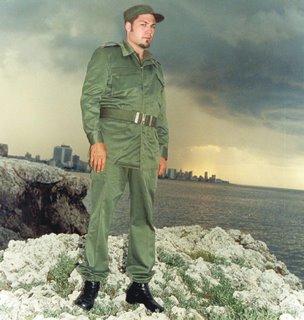

Now that my 2,000 word introduction is finished, I would like to share with you the story of my medical school interview. This was actually my third interview as I had previously applied unsuccessfully two years prior. Turns out that schools are not as amused as one might think when applicants show up in a high school counselor-style sweater and khakis rather than the traditional business garb, even if said applicant is tall, dark, and disarmingly handsome. Who knew?

So I sat, facing a random door in a large office space full of bustling admissions personnel and fellow applicants running like the proverbial headless chicken to find their next interview. I had already completed one interview with a 3rd year medical student at this particular school. He had been a little cool in his demeanor, but I soon broke through his shell, as I am a master of communication. It turns out (and at the time I had no idea that this is a scientific law even more bulletproof than evolutionary or germ

theory) that medical students like feeling superior. So all I had to do was ask a question about his opinions on different curriculum choices or the grading system at the school, and wait for his answer. At this point I eagerly lapped it up like manna in the desert, making sure he felt like a medical student demigod. After 10 minutes or so of this game, we spent the rest of the interview discussing the bars that he and his fellow students frequented when they were not studying their brains out. It went well.

Alas, I had spent my karmic capital on that half-hour of glory, yet I sat before the door of judgment completely clueless. All I knew was that I was about to be interviewed by Dr. X who was a faculty physician subspecializing in gastroenterology. Entering the interview, I knew that my acceptance was waiting for me. I was entitled to it, like Michael Jordan was assured his sixth NBA Championship. As the clock struck 3, I knocked gently on the door and slowly turned the door handle. I entered the tiny room, scanning it with my eyes before settling on my interviewer, his desk, and the lonely chair that sat across from him. He was a stout old man, bespectacled and adorned in the traditional long white coat that marked him as that rarest of creatures, a physician. He looked up from what I assumed was my applicant file, and gave me a penetrating glare. I took my first step into the room and he opened his mouth and shot forth a verbal volley the likes of which I had not been privy to since my years of living at home with a teenaged sister.

"From your application photo, I expected you to be a lot uglier. You looked fat."

I stopped in my tracks, midstride on my way to the seat and spent a millisecond weighing my options. I could either launch myself over the desk like the physical specimen that I am and teach him just how much physical punishment my "fat ass" could inflict, or I could take my seat like a civilized young man and forget he had made such a comment, hoping that it was merely his geriatric senility peaking through. The first in a long line of regrets in my medical career, I chose the latter.

The interview proceeded in much the same manner. I was forced to defend every choice made during my undergraduate career (who would have thought that minoring in English could have offended someone) and explain the evolutionary biology research I helped with in excruciating detail before having my role dismissed with the wave of a hand. I found myself attacked for any opinion or insight I tried to offer, even in my own preferences in employment (no, I did not strip for a living). I had made the statement in my application that I really enjoyed interpersonal interactions and developing long-term relationships (one of those half-truths I was telling you about) and had intimated without sounding entirely committed that I might enjoy a career in primary care with its psychiatric component. Now, being a specialist, this evidently enraged my interviewer. He repeated over and over again that a huge part of his job was developing relationships with patients and treating them psychiatrically. Fair enough, he knows what medicine is like more than me. I told him as much, but then added in a not-so-rare moment of Bad Doctor stubbornness "I'm sure you do all that, but a primary care physician is going to have more responsibility to treat their patients psychiatrically and socially due to the nature of the office visits and the illnesses that they present with." I probably would have been better off telling him that Perry Mason was a filthy commie.

Later, I found my race up for debate. Looking thoughtfully at the pile of papers that so perfectly summarized my 23 years of life's work sitting before him, Dr. X. stated, "You know, by looking at your application, I would have thought you were Native American. Do you think that a trick like that is going to help you get accepted?"

A little background might help place this ludicrous notion into context. I had attended a high school in a town near a tribal community college. Now this community college was open to anyone of any race, and it just so happened that my high school had an agreement with this college to get students college credit for advanced classes. I had earned some credits in this manner, and as instructed in the applications had listed

all of my college credits and the official name of the college at which it was earned. The only other mention of Native Americans or their culture in my application was in my transcript where I had taken a Dakota Literature class to finish off my English minor. The class had exactly three Native Americans attending it out of at least 20 students. Most importantly, in the race section of the application, I had clearly marked "caucasian." I guess he forgot to check that minor section before accusing me of race camouflage. Needless to say, I was mortified.

Finally it was time for the interview to end. I maintained the plastered-on smile that I had so heroically kept up throughout the interrogation and answered him when he asked whether I was going to make the 8 hour cross-state drive back to my hometown that night. "Yes," I meekly replied, "I am really looking forward to seeing some of the autumn leaf changes during the drive." Now, I ask that you look past the inherent lameness of my response and instead focus on his assertion that, "It's going to be much too dark out there to see anything. You'll probably have a really boring drive." At this point, I had had just about enough of his crap. I was exasperated, and without thinking blurted out, "Then I guess I'll just have to settle on playing chicken with the deer that try crossing the highway." He looked at me as if he would rather see me in his headlights than in his clinic as a student. Knowing when to cut my losses, I got up from my chair, thrust my hand toward him abruptly and lied straight to his face: "Thanks for your time. It's been really enjoyable." With that, I tucked my tail between my legs and ran and ran.

Needless to say, this is the school at which I earned my first acceptance, and also the school which I attend. Some may be shocked that I actually accepted a spot at the school after such an interview experience, but they would be missing that this is truly the final move that will checkmate my opponent in our battle of wits. I plan on taking a gastroenterology elective during my 4th year, when my MD is pretty much wrapped up. I'm going to seek out the kind, old man that interviewed me, shake his hand and thank him for all he did for me and my career. Then, I am going to watch him keel over in disbelief.

In closing, let me summarize this story for you in one sentence: Beware medical school interviews with people who have dedicated their professional lives to sticking probes up people's asses.